What do the birth of Yitzchak Avinu, the three cardinal sins,and marital relations all have in common?

Click here to download PDF

When Sarah receives the amazing news that she will give birth to a son at the ripe old age of ninety she reacts with tzchok, laughter. We find that when Avraham Avinu had a similar reaction in last week’s Parsha (1), not only was his laughter acceptable, but Hashem actually commanded Avraham to name the child Yitzchak, from the same root as tzchok (ibid, 17:19). In fact, a short time later Sarah herself uses the same word: “tzchok asa li Elokim – God made laughter for me.” (ibid, 21:6) without any negative reaction.

Later in the parsha, we find Yishmael m’tzachek, laughing. (ibid, 21:9). Rashi tells us that this means Yishmael was involved in murder, idol worship and promiscuity.

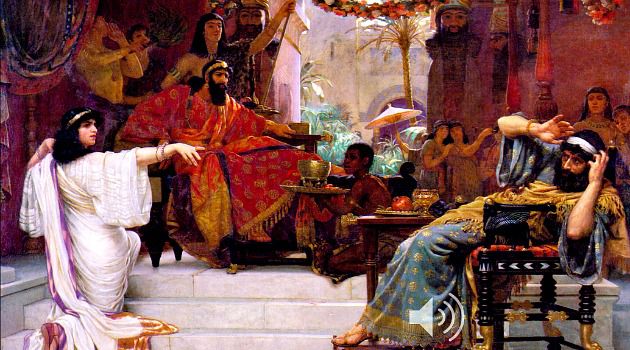

In Toldos, Avimelech observes Yitzchak m’tzachek with Rivka through a window (ibid, 26:9). Rashi tells us that he saw the couple engaged in marital relations.

The Torah applies the term tzchok, literally laughter, to all of these very different concepts. The question of course is, what does laughter have to do with all of these instances?

Breaking Boundaries of the mind

A close examination of these three occurrences reveals a striking common denominator. All of them involve breaking through the normal boundaries of logic. A concept that’s too large for the mind to contain or bear is tzchok. The absurdity of such events, the fact that they just don’t fit, is what prompts laughter, expressing shock or amazement.

Avraham and Sarah, aged one hundred and ninety respectively, were unable to reproduce by natural means. According to one opinion of Chazal Hashem did not make the couple younger to give them a son. They miraculously conceived despite their old age. This kind of miraculous feat is termed tzchok because it is not of this world. It is qualitatively different than healing Yitzchak and Rivkah from infertility at a much earlier age, for instance . We may not understand how Hashem healed Yitzchok and Rivka, but the event itself does not stagger the mind whereas Avraham and Sarah remained old and beyond childbearing age and still had Yitzchak!

Chillul Hashem

Yishmael’s behavior was also so shockingly out of the range of normal – but in a destructive way – that it is termed tzchok. Yishmael’s behavior was ridiculously evil, and has no place in this world. His three transgressions have a special halachic status which reveals their true devastating nature. All other sins, given extenuating circumstances like illness or extreme duress, are permissible. In other words, the world can “suffer” them.

But these three cardinal sins are forbidden even if it means giving up one’s life. When a Jew sacrifices himself like that, he creates a kiddush Hashem. On the other hand, willingly committing these sins is the greatest expression of chillul Hashem (2), which the Zohar describes as making a vacuum (from the root chalal) in the world that is seemingly devoid of Hashem’s presence. This is not merely bad, it is anti-reality – truly absurd and not in line with the world’s true existence.

Male – Female fusion

More subtlety, marriage and the relations that ensue can be described as tzchok because they defy cold philosophical logic. The Maharal (3) explains that this is why Chazal consider someone who gladdens the groom and bride as if he brought a todah (thank offering, brought when a miracle has occurred) sacrifice. The loaves of this sacrifice consist of both chametz and matzah, parallel to how the unlikely opposites of man and woman come together as one with marriage.

The Greeks went so far as to argue that opposite genders didn’t naturally belong with each other. To take such disparate forms and expect them to mesh in the ultimate unity is almost like asking “to square the circle”. We only view marriage as a normal state because the institution is so old. But the truth is, it is a type of miracle that deserves a toda offering. This great fusion of opposites is only something that Hashem can accomplish.

Forbidden Laughter

We see that tzchok is a reaction to the other-worldly in the fact that Chazal prohibited us from “filling our mouths” with it in this world (Brachos, 31a). Chazal derive this from the pasuk “Then (from the time of the redemption and onwards) our mouths will be filled with tzchok…” (Tehillim,126:2) We can only indulge in an attitude of tzchok occasionally in the time leading up to the redemption.

In the thousands of years before the times of Mashiach and a new world order, we are commanded to follow God’s instructions as defined by parameters the human mind can grasp.

Since the world is set to run with specific programs and laws, laughing is tantamount to declaring that the object of the laughter is outside these parameters. “There is nothing that does not have its place or time in this world” (Avos 4:3), but laughing makes it appear to have been stripped of its rightful place in reality and significance.

This world was created ex-nihilo, yesh m’ayin, but it now intentionally exists on a plane that only allows for yesh m’yesh. There is nothing truly newly created in this world, it can only be rearranged in a cause and effect manner. This is why in our parsha’s haftara Elisha commands the Shunamite woman to find something in the house, anything to start from. She had some oil, and Elisha miraculously brings forth her livelihood with that as its base. The miracle had to be minimized, to at least keep within the realm of yesh m’yesh – parallel to cause and effect that we can understand.

This principle is also manifest in the laws of prayer. If someone hears a cry of anguish in his neighborhood, he is forbidden to beg Hashem that it did not come from his home. What’s done is done, and praying for it to be otherwise would be to pray for a re-write of history.

In addition, after forty days from the creation of a fetus it is prohibited to pray to change the gender, as after that time on the gender has already been determined (Brachos, 54a;60a). Similarly, once a grain pile is measured it is prohibited to ask that blessing (that it should be much) should rest on it. (Ta’anis, 8b)

All of these are examples of the impropriety of asking for an established fact to “not be what it is”. Hashem certainly has the capability to alter this reality, as He did when Yosef was changed to Dina in Leah’s womb (4). But, once something has been actualized, our job as servants of Hashem switches from being those who ask, to those who thank (5).

In the future, when there is no service of Hashem, the world will revert to a super-logical type of existence, one that defies cause and effect. “Then our mouths will be filled with laughter,” because Hashem will unveil mind-blowing revelations.

Holy Laughter

But sometimes Hashem does give us a glimpse of His super-natural mind – bending management within this world. Purim is a prime example; it is the one holiday that will still exist in the world to come (6). The theme of the day is certainly robed in tzchok, whether it’s manifest in absurd costumes or the story of Megillas Esther itself, with its myriad twists and turns. The day that was designated for our annihilation became the day of our salvation; Haman built a gallows for Mordechai, and he was hung on it. The central mitzvah of the day is to attain a level of other-worldly awareness in which there seems no distinction between the blessedness of Mordechai and the cursedness of Haman. These are all matters that normal perception can never tolerate. Therefore in must be through intoxication, “ad d’lo yada – to the extent that one does not know…” because it is beyond the realm of normal da’as, knowledge.

My Rosh Yeshiva, HaRav Yaakov Weinberg zt”l argued that tzchok and lomdus in are reciprocal concepts. Lomdus seeks to draw together two seemingly disparate ideas, then to show the similarities between them. Quality humor – or tzchok – tags on a totally incongruent finish to an otherwise coherent tale. This is actually the foundation of the age-old tradition of “Purim Torah” – a pilpul of the absurd (7).

Midas Hadin

The world’s programming emanates from the Middah (Divine trait) of Din (justice), which Hashem used to temper His initial creation through the infinite will to bestow goodness. Unbridled Chessed (kindness), on the other hand, knows no bounds, order, or merit.

Din is what actually facilitates the whole concept of a middah, literally meaning measure, and implying a limit. It is what allows for the definition of what was unbounded, allowing it to be received by finite beings.

Chessed and Din superficially appear to be conflicting opposites. It seems unbelievable that Yitzchak Avinu, the embodiment of Din, could emanate from the Chessed-inspired Avraham.

The Torah sees Chessed and Din as being totally complementary. The Ramchal (8) explains that Hashem’s purpose for this world is bestowing unlimited good on His creations. The best scenario for this is when created beings earn their good, so they will not be embarrassed by unearned reward (known in Kabbalah as nehama d’kisufia, bread of shame). When a person earns his reward, he is becoming complete and whole, moving towards a likeness of Hashem. He is then able to connect to Him, which is the ultimate good.

When Hashem sends Din into the world the Din doesn’t annul Chessed – it is the full degree of Chessed to be manifest. Din puts Chessed in appropriate boundaries – the effect will be according to the effort. Clothing Chessed in Din actually gives us the ability to acquire an otherwise unattainable portion of unlimited goodness (Ain Sof). The world runs via Din which results in the laws of nature that provide us with the opportunity for performing mitzvahs and acquiring this unceasing reward (9).

Yitzchak’s Laughter

This way of running the world is a type of manifestation of tzchok, the two opposites of Chessed and Din cooperating in order to provide an arena for service of Hashem.

Avraham greatly desired a son who would complement his service, thereby acquiring a completeness that guaranteed continuity. The idea that Yitzchak Avinu firmed and bolstered his father’s accomplishments by giving Chessed a lasting base with Din is hinted at when the Torah recounts how Yitzchak reopened all the wells his father. (Bereishis, 26:18).

Chazal say that ironically Yitzchak is considered our spiritual father more so than Avraham and Yaakov (Shabbos, 89). He is the unlikely future and final defender against the claims that Klal Yisrael are undeserving, while the other patriarchs are portrayed as abandoning our cause. Yitzchak, representative of Midas HaDin, saves us by arguing that we are Hashem’s children and therefore deserving of mercy! That’s tzchok, and the reason why Avraham’s son was thus named. The Gemara continues to say that it will be Yitzchak who, in the world to come, sees Hashem and points Him out to us. His Middah of Din makes the invisible Hashgacha of Hashem operate on a frequency that is visible to Klal Yisrael in Olam Habah.

This why Yitzchak, the vehicle of Midas HaDin, is named after “Tzchok”.

It is nothing short of Mind – blowing how this middah which judges and constrains actually brings the infinitely powerful and kind Divine Will to bestow infinite goodness to fruition and guarantees our eternal existence!

Good Shabbos

(1) Bereishis, 17:17

(2) Rambam, Hilchos Yesodei Ha’torah chapt. 5

(3) Nesivos Olam, Nesiv Gemilus Chassadim, chapt. 4

(4) See first opinion in Brachos, 60a.

(5) See Aruch Hashulchan, Orach Chaim, 230:1.

(6) See Rambam end of Hilchos Megilla.

(7) Heard from Rabbi Yaakov Weinberg zt”l

(8) Derech Hashem, 1:2:1

(9) This meshing of Chessed and Din even gives us the ability to maintain a grasp on the chukim, statutes, of the Torah that are seemingly beyond comprehension. Combining meat and milk, for example, is a chok, but it comes into this world clothed in the garb of the Torah, which provides with an opportunity to delve deep and wide (m’falpel) in its parameters.